09 Nov Let’s Go Shopping! Ethics in Procurement Part II, By Whitney Gray, MA, GPC

Imagine this hypothetical situation: Your organization recently won a large grant award ($200,000) and plans to use the funds to construct a new playground for the children it serves. The organization’s board is rightfully excited about the grant award and the positive impact the playground will have on the organization’s outcomes. The board and executive leadership of your organization call a playground company that is well-known for top-of-the-line equipment and start designing the playground. The vendor has the specific play structures necessary for the special needs of the children served by the organization. For proper installation, elements of the playground structure will need to be set in concrete foundations. One board member owns a concrete company and offers to do the concrete work. The grant funds are quickly expended, a beautiful playground is built, the children served by your agency take great enjoyment from using the playground, and the funder is delighted when a representative conducts a site visit.

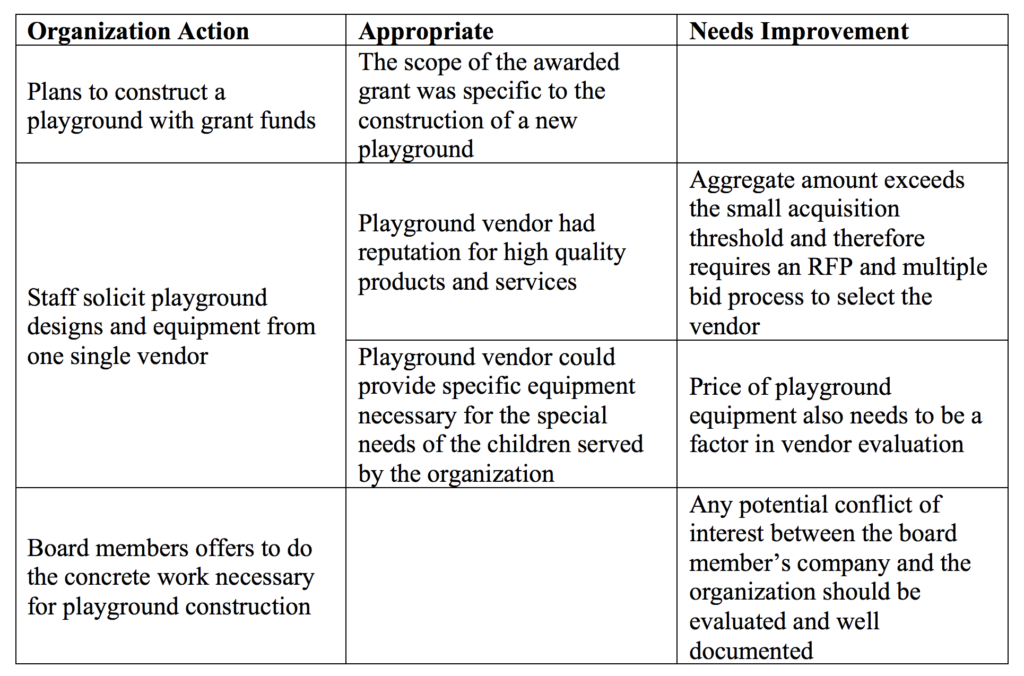

As the grant professional, it is our responsibility to guide the organizations with which we work through all of the nuances of situations like the one described above. A working knowledge of federal procurement standards and their application to non-federal awards is essential for ethical post-award implementation and management. When your organization establishes all of its procurement policies around federal guidelines, you can rest assured that the strongest ethical standard is met. Here are three areas where the hypothetical organization appears to be out of compliance with federal procurement standards.

- The organization did not have existing, documented procurement policies and procedures for large equipment purchases;

- The organization’s staff only utilized one single vendor for the design and purchase of the playground equipment; and

- There is a potential conflict of interest with the board member’s concrete company doing the work.

Course Corrections

Since ethical considerations are not always strictly black and white, it is helpful to identify what the organization did well in the hypothetical scenario described above and where there was room for improvement. The ethical grant professional can certainly apply a reasonable interpretation to the applicable law and funder guidelines to help their organization navigate the gray areas of a situation.

RFP and Multiple Bid Process – The purpose of this process is to increase competition, fairness, and price competitiveness between vendors to ensure the grantee organization receives quality goods and services at the best possible price (2 CFR 200.319). Federal guidelines give a clear outline of what this process should look like, in a variety of situations (2 CFR 200.320). The grant professional should diligently work with the organization’s leadership to ensure these practices are included in the organization’s internal controls and are practiced as applicable.

Cost vs. Quality Evaluation – Anytime multiple vendors are solicited for bids there will be differences in the cost and in the quality of the goods and services proposed. The organization should have a clear method for evaluating cost vs. quality when making its final vendor selection. Federal guidelines are clear. In most cases, this decision is ultimately at the discretion of the grantee organization, but the rationale for selecting one vendor over another must align with applicable law, avoid conflicts of interest or the appearance of conflicts of interest, and be clearly documented (2 CFR 200.320(d)(1-5) and 2 CFR 200.323).

Assel Grant Services has developed a vendor evaluation tool that you can customize to meet the needs of your organization. You may download this template for FREE and use it to assist your organization in developing federally-compliant and ethical procurement procedures.

Click Here to Download Vendor Evaluation Tool

Potential Conflict of Interest – In the scenario above, the organization can avoid the appearance of a conflict of interest or an actual conflict of interest with the board member and his concrete company in one of two ways:

1) The board member can donate the cost of materials and labor to the organization as an in-kind donation which the organization can cost share for the total playground installation cost, or

2) If the organization intends to pay for the concrete work, it can issue an RFP and the board member’s company can respond to the RFP with a competitive bid.

In either case, the organization should document its relationship with the board member’s company in the grant management records. In the event the organization issues an RFP, it should be careful to avoid using the board member’s knowledge to design the project requirements such that the board member’s company will be the only competitive vendor. Additionally, the board member’s company’s bid should be evaluated objectively along with all other vendor bid received (2 CFR 200.112). The vendor evaluation tool provides an objective framework that takes into account pre-existing relationships between an organization and members of its governing board.

At the end of the day, the grant for playground equipment described in this scenario actually occurred in an organization where I worked early on in my career. The leaders of the organization made every effort to conduct business in an ethical manner. The grant award was a significant win for the organization – from both a financial and funder relationship perspective. While shopping for the new playground equipment, the project director added several custom pieces to the playground that delighted the children it was designed to benefit. Because the board member donated his company’s labor and materials cost for the concrete work, extra grant funds were available in the budget for higher-priced items like a metal slide and planting a large shade tree. Ultimately, every purchase passed the JAR (Justified, Allocable, and Reasonable) test described in Ethics and Procurement Part I. Just as importantly, the children loved their new playground and because of the success of the project, the organization received additional grant awards from the funder.

GPCI Competency #6: Knowledge of nationally recognized standards of ethical practice by grant developers. Skill #01: Identify characteristics of business relationships that result in conflicts of interest or give the appearance of conflicts of interest. Skill #02: Identify circumstances that mislead stakeholders, have an appearance of impropriety, profit stakeholders other than the intended beneficiaries, and appear self-serving.

GPCI Competency #5: Knowledge of post-award grant management practices sufficient to inform effective grant design and development. Skill #01: Identify standard elements of compliance. Skill #05: Identify effective practices for key functions of grant management.

Additional blogs in our Ethics series:

What if You Have Too Much of a Good Thing? by AGS Staff

Let’s Go Shopping! Ethics in Procurement, Part 1 by Whitney Gray, MA, GPC

Above All Else, You Must be Honest by AGS Staff

Don’t Just Write It, Cite It: Ethical Research in Grant Writing by Leah Hyman, GPC

Building an Ethical Foundation for Your Funder Relationship by AGS Staff